WATER

Loom House earned the Net Positive Water Petal from the Living Building Challenge by providing all of the water we need and treating on site all of the home's grey and black water. The treated water is cleaned by the earth and reenters the Bainbridge aquifer.

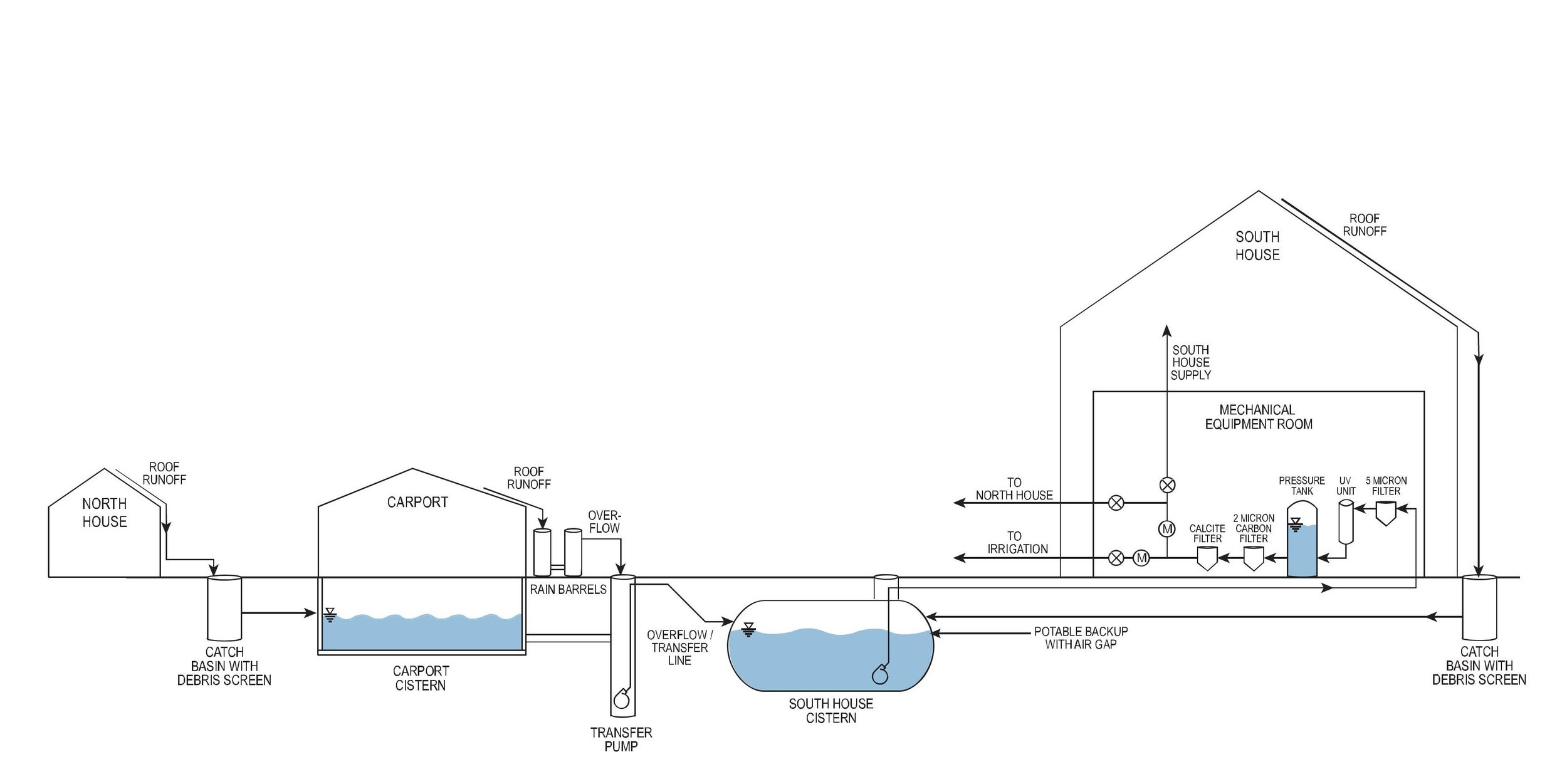

Rain water to potable water design by Biohabitats

Twin Corten Steel Rain Barrels hold a total of 800 gallons

Water turned out to be the most complicated issue for us in redesigning the home. It affects nearly every other system. For example, water consumes energy when we transport it in sewer lines, clean it and send it back out to homes. Transporting and treating water uses approximately one-third of society's total energy. But there are other big implications of whether we allow water to fall to the ground, nourish the soil and sink slowly into the aquifer.

The day before we received our building permit, the Bainbridge City Council announced a moratorium on all new development on the island. The biggest stated reason? They feared that the source of Bainbridge's water supply -- it's aquifer -- was imperiled by the development.

Loom House achieves water self-sufficiency by collecting and treating water more strategically than a standard city-sewer hookup. (If we catch our roof water and send it into the sewer lines, we are mixing clean water with waste water, and are forced us to clean the whole batch.) Instead, the house collects rain water from the car port and the South House. The car port water lands in two above-ground 400-gallon weathered steel cisterns and will be used for watering the vegetable garden. The South house water lands in an underground 10,000 gallon cistern. No pumps (or energy) are used to move the water. Gravity does the work. We also installed a back up connection should a future owner want to connect to the city water line.

When someone in either house turns on the tap, water moves from the cistern at the South house into the mechanical room there, where it is filtered and disinfected for indoor use. The disinfecting is done by a Ultra-violet light – similar to using a UV light to disinfect water at a camp site.

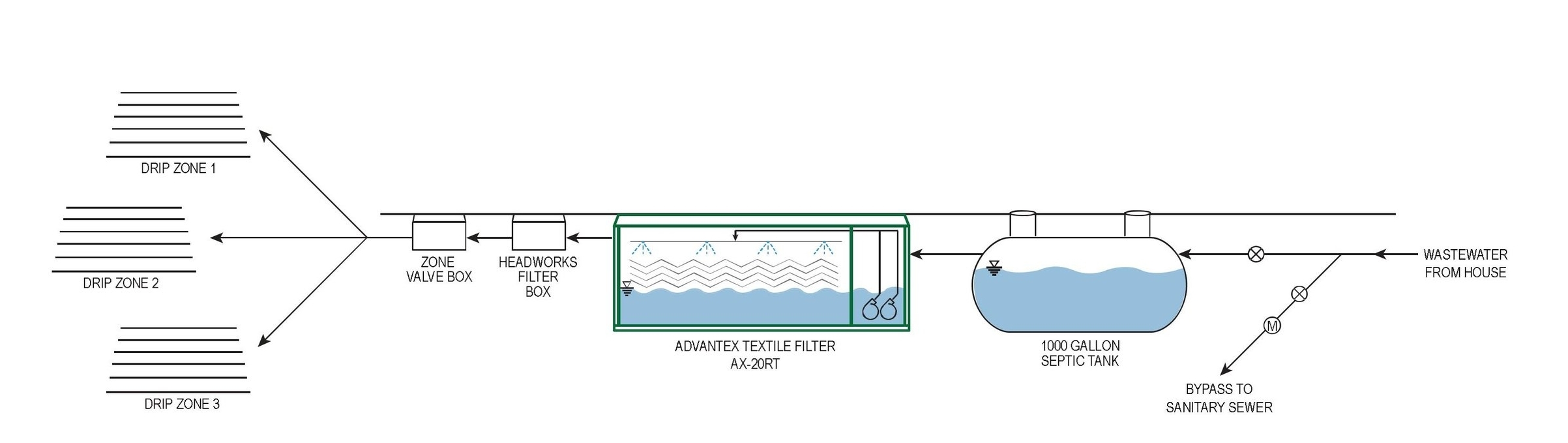

Wastewater design by Biohabitats

The Magic Textile Box

To qualify for Living Building Water Petal certification, the house had to also treat all of its own wastewater. We wanted to keep the system as simple as possible, and Biohabitats delivered beautifully. Unlike many water-saving homes, we did not install composting toilets but use regular, low-water flushing Totos. The on-site treatment is a simple, glorified septic tank. (As Pete Muñoz of Biohabitats says, “A septic tank is a remarkable machine as long as it’s not asked to do something it’s not designed to do.”)

The waste runs from the house to a septic box, where “solids” drop out. Next, instead of moving directly into a septic field buried deep in the ground, it flows into another box, which has layers of textiles that hold beneficial bacteria. These bacteria feast on the pathogen-carrying micro-organisms. A small, one-half-horse-power, pump circulates the water until the water reaches a high quality. Once clean, the effluent is dispersed to a drainfield in three drip irrigation zones.

The system is remarkably low maintenance. The textile filters never require replacement, and the pump is designed to last 30 years. Every five years, someone checks to see if the first holding tank needs to be pumped and rinses the beneficial bacteria off the filters. The rinse water stays in the tank to allow the bacteria to recolonize. The system also sends monthly quality reports, via a telemetry, or cellular-phone-like, hookup. And should an emergency occur (a pump breaks, for example), the system calls immediately for repair.

Kitsap county approved the design as described above. However, the City of Bainbridge refused to approve the system unless we satisfied a specific requirement in the city code: any house within 300 feet of a sewer line is required to send its toilet water to the public sewer. We modified our design to connect toilet water directly to the public sewer, but, should city code change, we will have a valve that allows us to redirect that water for onsite treatment.